The unseen barriers Black creators face in going viral, how their moments lead to less success, and why chasing virality is a losing game.

Thanks to all of you who were here for edition #2 last week, where we sent this out to 79 readers. As I write this, the edition is going out to 83 readers. Not quite the percentage climb we saw in Week 2, but a climb nonetheless.

Obviously, as a creator myself, I have to be in the business of growing my reach, and these week to week gains are certainly something I’m keeping track of. This week, I’m committing to 2 or 3 growth tactics I’ve been exploring, in addition to what I’ve been doing on LinkedIn. If you’re interested in my own personal growth here with The Culture Economy newsletter, let me know, and I’ll share more of what’s going on there!

Now, let’s get this started!

In the first two editions of this newsletter, we’ve been tackling virality, as part of my The Virality Paradox series. In those editions (Part 1 & Part 2), we’ve answered the following questions:

- How do we define virality?

- What makes virality so magical?

- How do algorithms decide who goes viral?

- Why is it getting harder to go viral?

- What actually happens after you go viral?

- What’s going on with Ashton Hall?

This week, I finally give you somewhat of a break and my usual 3k words will be cut in half, as we’ll only answer one question:

- What is the Virality Paradox?

It’s the question behind the whole series—but the answer isn’t obvious. Sure, by now, most people know that virality is no longer the name of the game. But do they know why? How it came to be? And why it’s of particular issue for Black creators?

So far we’ve talked about how virality happens, why it’s harder now than ever, and how it’s not to be relied upon.

But we haven’t discussed how the virality game isn’t just different for Black creators…

It’s rigged.

And the result is what I call The Virality Paradox—a frustrating and all-too-familiar paradigm that Black creators must avoid.

What is the Virality Paradox?

The Virality Paradox is when Black creators go viral—but don’t experience sustained growth, long-term monetization, or industry-level success.

And while yes, there are exceptions—Black creators who broke through, non-Black creators who faded fast—this isn’t about absolutes. It’s about systemic realities. Because for Black creators, virality often isn’t the beginning of a journey—it’s the peak.

It’s Hard to Be Black and Go Viral

Earlier, we talked about how a viral post goes from small test groups to massive reach based on engagement.

But what if you’re Black?

That process (systemically) breaks down in a few key ways:

Algorithmic & Artificial Intelligence Bias

Studies show LLMs and algorithms disproportionately associate Black content with negative traits. Platforms have flagged African American Vernacular English (AAVE) as “inappropriate.” TikTok’s own team acknowledged deprioritizing #BlackLivesMatter content. Worse, non-Black users often used the same tags without penalty.

When algorithms run the show—and those algorithms reflect societal bias—Black creators are forced to play a rigged game.

Lack of Network & Resources

Many viral creators break through because they’re part of tight-knit cross-promo squads—content syndicates, influencer pods, etc. Historically, those groups have been largely white, well-connected, and closed off.

On top of that, Black creators are more likely to lack resources—high-end equipment, editing tools, even the free time to post consistently. That makes it much harder to pump out the steady stream of content virality often requires.

Platform Priorities

Platforms have a bias towards advertisers, and ultimately, they give them what they want. For example, when TikTok started racking in some ad money, YouTube got in the short-form vertical race and started pushing Shorts our way.

But what do advertisers want most?

Brand safe content.

Of course, “brand safe” is sometimes like porn—you think you know it when you see it, but everyone’s definition is different, and brand safe just ends up meaning white-adjacent. So when platforms juice visibility for content they think advertisers will like… culturally specific Black content gets sidelined.

#PeakBlackCreator

Even when Black creators do go viral, they often peak faster. Why?

Shorter Runway

In my time working at BlackOakTV and YouTube, I’ve talked directly with over 100 Black creators (and many more non-Black creators). And in my encounters, the likelihood of a professional Black creator not having a team, agent, or brand representing them is much higher than it is for a professional white creator.

That means no one is following up with the media, pushing clips, and strategizing what’s next in a way that extends the wave of virality the way Flyana Boss was able to do, because in part, they did have a team behind them.

Monetization Doesn’t Scale

Ads don’t pay well unless your content is deemed “safe,” and Black creators are more likely to be demonetized or blocked from monetization programs altogether. A Zippia study found that just 3% of YouTube’s Partner Program creators are Black—despite making up 13% of the U.S. population.

Even brand deals, which could fill the gap, fall short: Black creators make 35% less than their white counterparts, per deal—and that’s if they get paid at all.

Of course, ads and brands aren’t the best ways to monetize viral moments—products, services, transactions and connections are. Unfortunately, if you’re a marginalized creator, you’re less likely to have the time to set these up during your growth stage.

Culture Vultures

Black creators disproportionately create the most engaging content we see on social media, but inevitably and incredibly, that creativity is often stolen, mimicked and disconnected from its original creator.

Addison Rae, with 88 million TikTok followers, infamously went on Jimmy Fallon and performed multiple dances—most of which were choreographed by Black women such as Keara Wilson, Jalaiah Harmon and Mya Nicole—and didn’t credit the originators. This is not an accident. It’s a system—one of cultural appropriation perpetrated by bigger, mainstream creators for the purposes of fame and money.

Chasing Virality Is a Losing Game

Even if you’re not Black, virality is not something creators can rely on in 2025. In fact, I’m here to say that 99% of time (not a real stat), virality—by itself—is a losing game. Why?

- It’s Random. Betting on virality is like building a business on lottery tickets.

- It’s Exhausting. You’re chasing trends, and even if you “catch” one, it resets the clock.

- It Doesn’t Build Equity. Viral traffic isn’t ownership. It’s a flash, not a foundation.

- It Delays the Real Work. You’re chasing attention, not building community.

At the end of the day, virality offers visibility, not value. Yes, being in front of a lot of people has value, but only if you can extract it. And frankly, most normal people can’t extract that value before the virality fades.

Don’t Believe Me, Just Watch

Doggface208

He rode a viral wave on a skateboard with cranberry juice. Got some quick cash and cameos. But he ignored DMs. Had no follow-up content. Didn’t work the press. And today, with 7.5M followers, he’s mostly averaging a few thousand views per post.

Jalaiah Harmon

Harmon, who I mentioned earlier, did become quite famous as a result of going viral. She spent months training, working on new dances, participating in collabs, all in the hopes of going viral for a dance. And she did, creating a dance for K CAMP’s “Renegade” that got 13,000 views on Instagram overnight. But when it got copied by someone else on TikTok, only for mega influencer Charli D’Amelio to post it without crediting her, Harmon’s budding viral moment was cut off at the knees.

In the end, Harmon ended up with 600k followers, as she was lucky—people fought for her. But without the culture’s intervention? She might’ve never escaped the Virality Paradox.

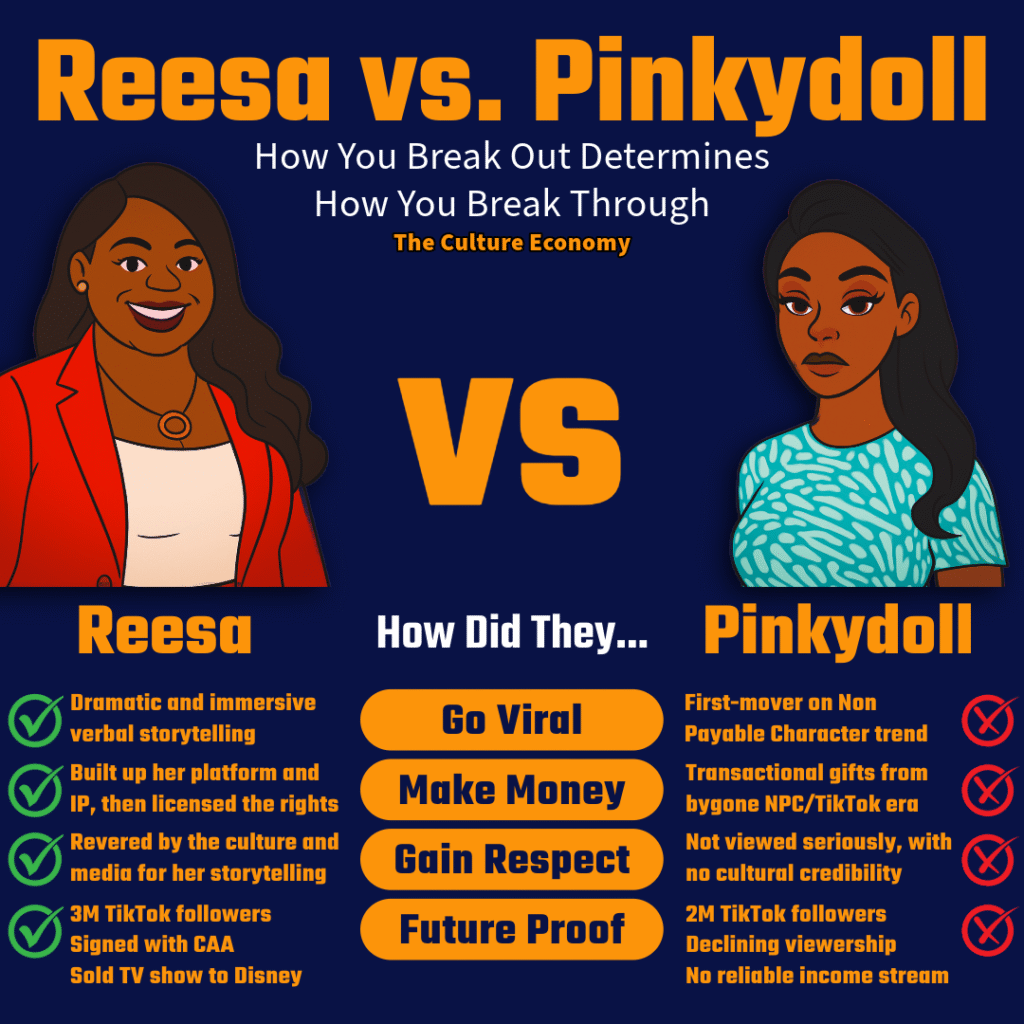

Reesa Teesa vs. Pinkydoll

Of course, the best way to exemplify the Virality Paradox is to show the dichotomy between two creators of different paths. Insert Reesa Teesa and Pinkydoll.

How they went viral?

- Pinkydoll: Took advantage of the non-playable character (NPC) trend and went viral with livestreams featuring hyper-performative take on the format.

- Reesa Teesa: Went viral for her uniquely relatable telling of a dramatic, 50-part, 500-minute TikTok storytime saga about her disastrous marriage that was raw, cinema-worthy and emotional.

How they made money?

- Pinkydoll: The beauty of Pinkydoll’s rise was that it was built on making money—she got paid for every NPC role she played, reportedly making up to $10k per day. But the nature of her content wasn’t suited for ads/brand deals, or long-term monetization after the NPC trend died out.

- Reesa: She didn’t immediately make money, as she wasn’t in TikTok’s monetization program. However, because of the respect for her story and storytelling capabilities, eventually brands and Hollywood came calling—she has a TV show in development.

How were they received?

- Pinkydoll: Chasing an extreme trend cost her cultural credibility. She became a meme, and is now attached to “Love and Hip Hop”—a move many fans are bemoaning.

- Reesa: Is taken seriously by mainstream media, cultural commentators, and fellow creators. She’s now working with the very much respected Natasha Rothwell.

The Virality Trap vs. The Social Launchpad

With nearly 2 million followers on TikTok, it’s hard to believe someone is professionally trapped, but with the NPC trend gone, it’s hard for me to look at Pinkydoll in any other way. She has a Linktree with a little of everything: courses, Twitch, a fledgling YouTube channel, OnlyFans, and an address in Quebec Canada to send gifts. But no roadmap for long-term value.

Reesa has a show in development, IP to monetize, and real brand partnerships. She didn’t go viral and get lucky—she built a story that was built to last and could carry her forward if it got in front of the right audience. And she displayed a storytelling skill that ought to be high in demand.

No, Reesa didn’t do things perfectly. She didn’t immediately find a way to own or monetize her audience. But she came with substance, format, consistency, and a tentpole moment to rally around. In short, she created a launchpad. And now that she has taken off, the sky is the limit.

Unfortunately, Pinkydoll suffered the fate of the Virality Paradox. Yes, she’s better off than she was before, but also—as it relates to her NPC high—she has peaked. She owns no IP. She has no publicly acknowledged skill. She has no cultural credibility. And the path forward is nebulous, at best.

Like a lottery winner, she cashed in. But like a lottery winner, she appears to be crashing out.

And it all could’ve gone differently had she made the strategic shift.